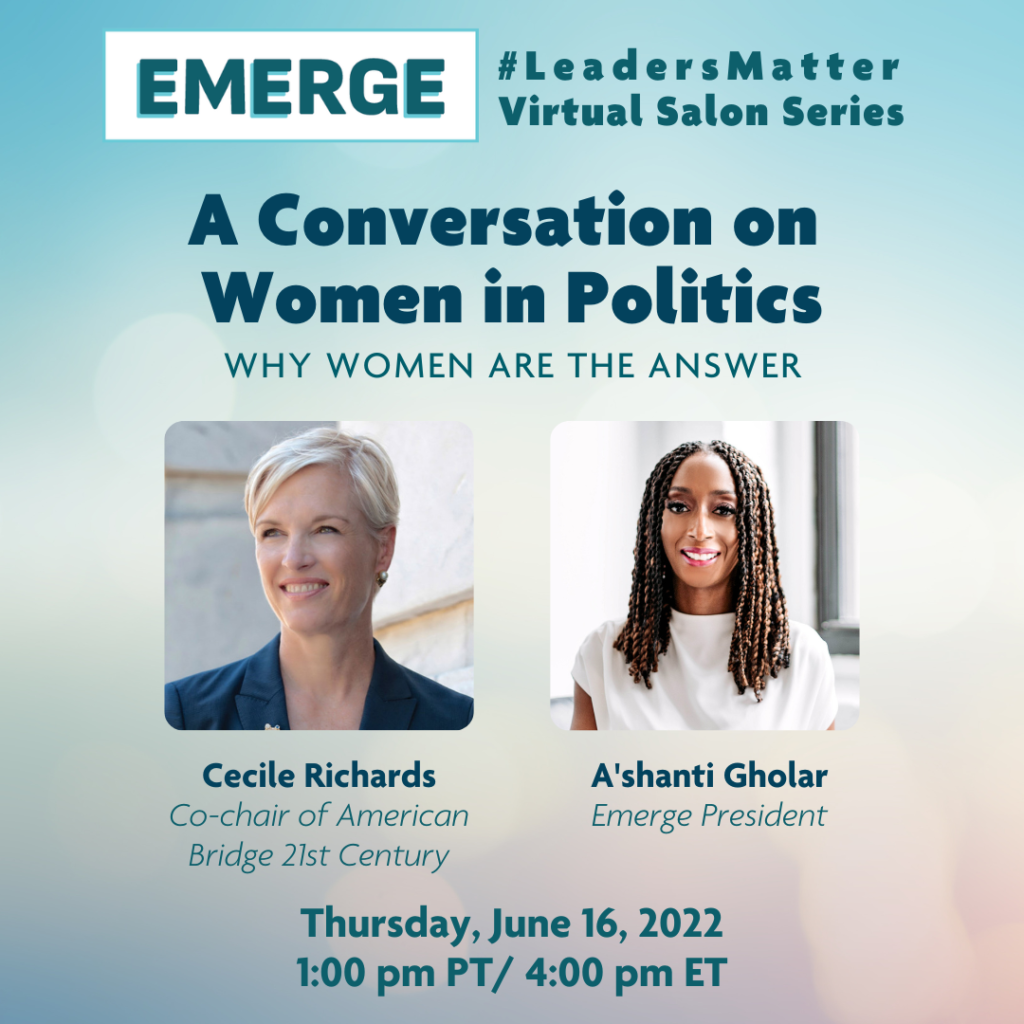

What’s next for the abortion rights movement? For many of us, this is the question at the forefront of our minds. Join us for a timely conversation between Emerge President A’shanti Gholar and Cecile Richards, Co-chair of American Bridge 21st Century. Cecile is also the Co-Founder of Supermajority, and former President of Planned Parenthood Federation of America. Hear from these two incredible women on their thoughts on the fight for reproductive freedoms, the long-term strategies Democrats need to adopt, and steps we can all take to protect women’s rights. You won’t want to miss this!